Lessons from a garden

When I arrived at my grandfather’s house in Baltimore for a visit in June, I found the front door unlocked and the house empty save for the dog, who, after a few minutes of coaxing, warily let me pass. The scene was unnerving given the circumstances—my grandfather had recently been admitted to home hospice care following a diagnosis of advanced bladder and lung cancer—and I immediately assumed the worst. But I always assume the worst.

This time, my panic was unfounded. I found him in the backyard watering his vegetable garden, looking content even as he shuffled precariously over the uneven ground, using a hoe for support. He had attached his catheter bag to a rope that he had slung around his neck, a cumbersome arrangement it seemed, but he would later tell me that wearing the bag on his belt just made his pants fall down.

When he finished his watering, we sat down next to a murky koi pond to talk. I took note of the scrapes and bruises on one side of his face, evidence of a recent fall. That unsteady gait was going to be a problem, I thought. He handed me some fish flakes.

“Let’s see how many are still alive in there,” he said.

I scattered the food, and we sat in silence for a few moments, waiting for the fish to emerge. The midday sun was punishing. I could feel my upper lip begin to sweat from the heat, but my grandfather seemed perfectly comfortable in his long-sleeved flannel shirt and worn corduroys. I urged him to drink some water to avoid overheating, but he waved me off, still focused on the fish.

When the koi finally rose up from the algal goop to begin feeding, proof that nature can overcome a fair amount of neglect, my grandfather looked up to survey his yard and sighed.

“What kind of fool plants a garden he won’t live to harvest?”

* * *

Nature abides by her own whims. And we are never guaranteed the harvest. Making plans for the future is an act of faith at any age, but planting a garden at 91 while terminally ill strikes me as something different from faith. It is not a fool’s errand as my grandfather believed, it is—to me—the purest form of kindness, a demonstration of love for those who will share in the fruits of our labor, regardless of whether or not we are able to join them at the table.

My grandfather, frail as he was toward the end, could not be discouraged from venturing out, risking a fall that would certainly hasten the dying process, to perform this daily meditation of tending. He was intent on finding joy and purpose in the work of each day.

He had always been able to find joy, even in the starkest circumstance. I can recall him once standing outside in the dead of winter actually whistling while he worked, and he was something of a virtuoso at it, trilling like the birds he adored as he chopped wood in the snow. I still think of this music sometimes when I grow weary of my own work, and it reminds me to look for the joy in my task. It is always there.

I wanted to say all of this to him. I wanted to offer comfort. I wanted to tell him that if he is a fool, he is the wisest fool I’ve ever known. But the silence between us was a comfortable one. Instead, we just held hands.

* * *

Later that afternoon, when the sun had dipped closer to the horizon and cooled us, I plopped down under a mulberry tree and stared up at the clouds, trying to will them away with my mind. My grandfather convinced me that I had this power when I was a child, and I was eager to reminisce with him.

“Remember the clouds?” I asked, recounting the story.

“Like it was yesterday,” was always his reply when prompted with a memory—now the call-and-response incantation of the dying. Over the next few days, we said it like a prayer.

Remember when you ran away from home at 14 to work on a riverboat? Remember that girl at the pool who thought your name was Popeye? Remember how you always let me shave your head every summer? Remember your cure for the hiccups? Remember?

Like it was yesterday.

So many things come to mind when I think about my grandfather, how he’d pull green onions from the earth and dip them in a plate of salt before eating each stalk whole, how he’d dutifully trek out into the snow to feed the birds throughout the harsh Pennsylvania winters, how his door was always open to everyone, including countless foster children and hapless family members in need of a hand.

As I grew older, we would sit by the fire late into the night and talk about philosophy and science fiction and dystopian futures, mulling over thought problems I now pose to my children. He shared his hard-earned wisdom with me. He saw me through heartbreak and gave me away at my wedding. Later in life, he delighted in his time with my children, and they, in turn, delighted in his mischievous sense of humor.

But mostly I remember the quiet moments—holding hands in the garden or standing together to watch the birds peck at their feeders. His presence, his unfailing commitment to people, that is what I carry with me. In this way, he showed me the face of love.

* * *

Back at home, my tomatoes and squash are thriving, but some of the tender lettuce is bolting as the summer weather finally settles in. Nature is a marvel in how it knows when its time is up, sending up one final burst of blooms before scattering itself to the wind to be reborn. But maybe this instinct is in all of us.

As I said goodbye to my grandfather before heading off to the airport, I suggested that I could return in August so that we could eat the tomatoes from his garden together. He smiled.

"That would be nice," he said, patting my hand, "but I'm sure I won't make it to July."

And he didn't. Two weeks later, another fall sent him to the hospital, and he died there on Father's Day evening. He had asked for no memorial services, and the state Anatomy Board took possession of his body, which he had donated for the benefit of posterity, one final gesture to serve as the capstone to a profoundly selfless life.

* * *

Tonight, I am harvesting zucchini, as I will do every night for the remainder of the summer. As I snap a few squash from their stems, I play with my grandfather’s words in my head: What kind of fool plants zucchini I think to myself, and I laugh at how quickly we come to regard abundance as a burden. Have I regarded the years this way as well? Perhaps I should reflect on my grandfather’s experience and begin each planting season believing it to be my last. That way, I could never see abundance as anything other than a blessing.

I wish I could share one more harvest with my grandfather, if only to dazzle him with the 57 ways I have learned to prepare zucchini over the years. But I know he will be with me through every season, helping me take pleasure in the work of each day by planting a whistling tune in my ear, one that I will try to recreate but that I will never quite be able to match. And he will be with my family at the table this evening as we laugh and talk and live out this abundantly joyful life, one made possible, in part, through his example of unconditional love.

My grandfather cultivated a life of kindness, generosity, and care, and I am the lucky beneficiary of that labor. And though I’d give anything to sit with him and taste the tomatoes he was tending in June, I take comfort in knowing he is sharing that final harvest with his beloved birds.

This essay first appeared in Still Point Arts Quarterly.

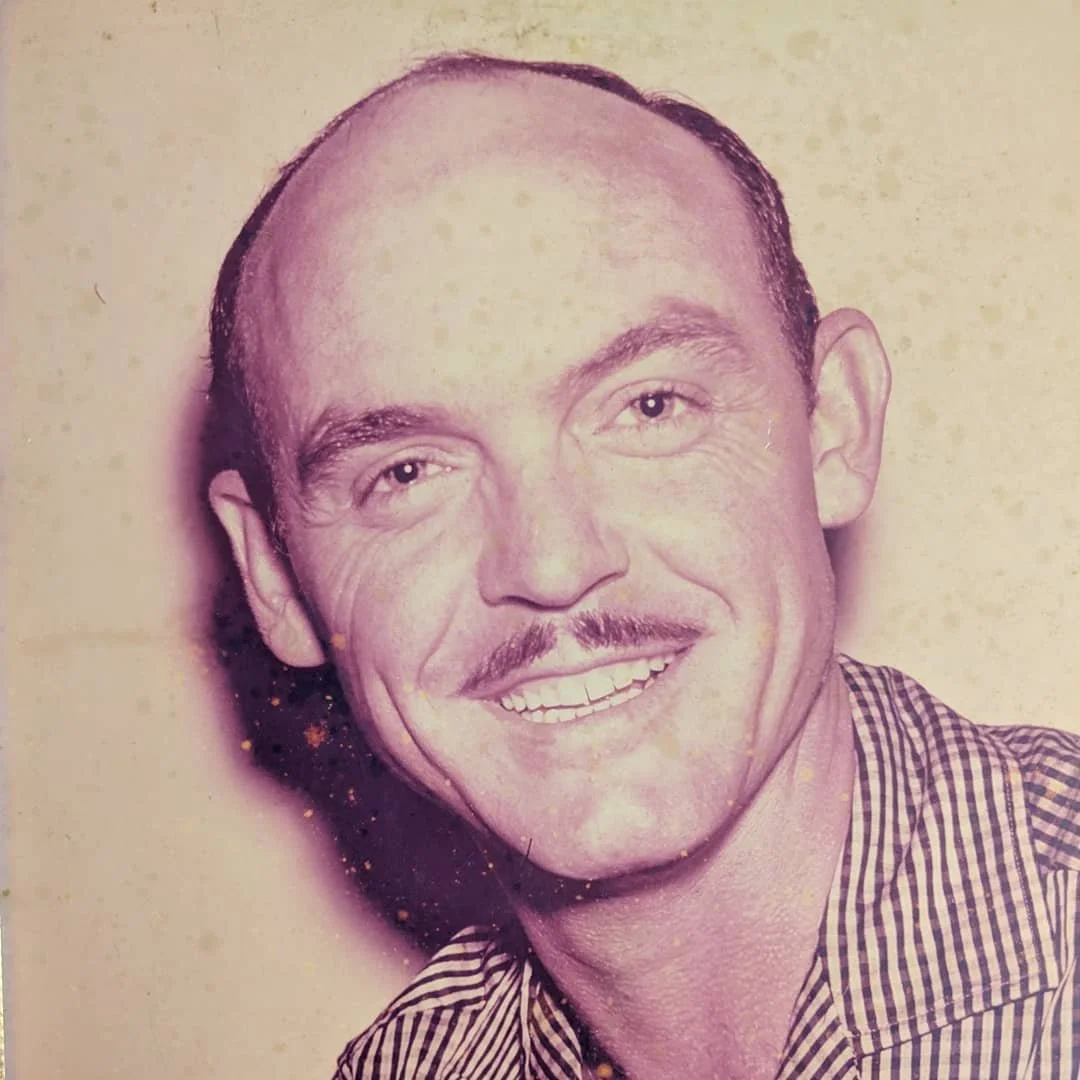

Dutch—known to me only as Poppop—married my grandmother Lillian and raised her three boys as his own. He taught me most of what’s worth knowing in life and remains one of the best men I’ve ever known.

Willis Orville “Dutch” Gleason